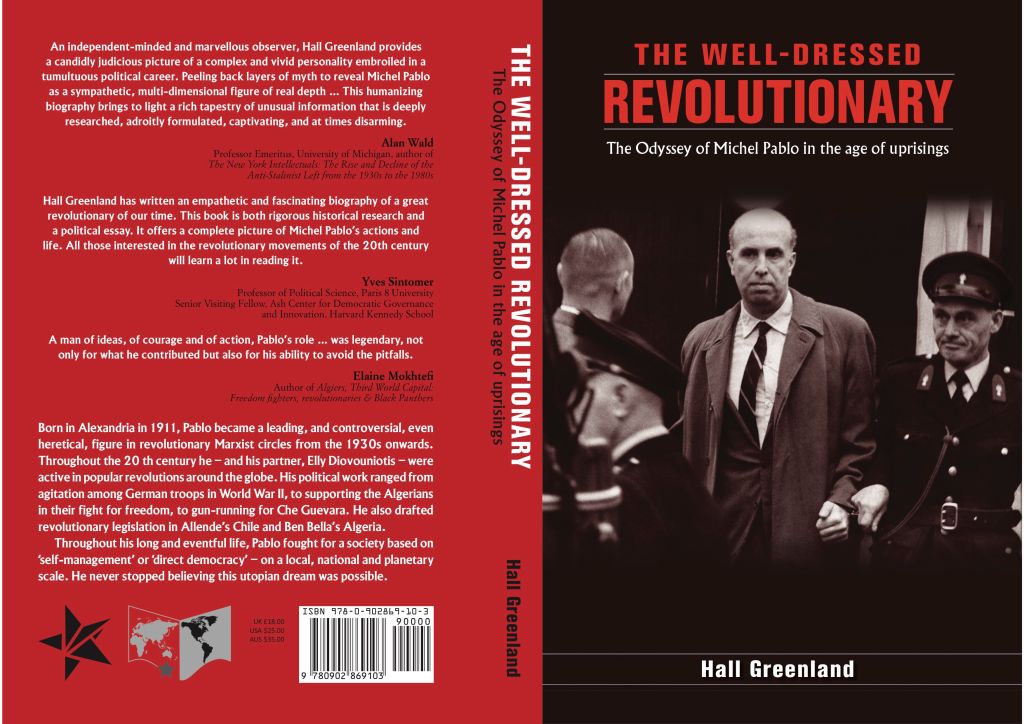

The Well-Dressed Revolutionary: the Odyssey of Michel Pablo in the age of uprisings (Resistance Books, London & IIER, Amsterdam, 2023) 376 pages, rrp $A35.00, $US25.00, £18.00

ISBN 978-0-902869-10-3 (Also available as e-book from online retailers.)

April 2024 Hall Greenland, author of The Well-Dressed Revolutionary, talks about the book to Caroline Baum on the Life Sentences podcast. Caroline interviews contemporary biographers and reveals the answers to the central question – “What is the secret to writing a really readable biography?” See link here

The Well-Dressed Revolutionary is available from the publishers at resistancebooks.org,

the usual internet outlets, London and Athens bookshops, and Gleebooks,

Resistance bookshop and Gould’s in Sydney, Readings in Melbourne

and the New Morning Bookshop in Adelaide.

Most bookshops will take special orders.

A short video intro to the book by the author can be seen here

Latest review from US magazine, Jacobin, 25 March 2024, link here

An engaging review of ‘an unorthodox Marxist’, link here

Radio interview with Col Hesse here

My biography of the legendary revolutionary Marxist thinker and activist, Michaelis Raptis (whose nom de guerre was Michel Pablo) was published in October in London.

An enthusiastic and standing room-only Sydney launch was held on 8 October at Balmain Town Hall.

The launch speech by Nick Riemer can be read here …

And a video of Nick’s speech is viewable here

The video of the author’s remarks and a reading from the book can be viewed here.

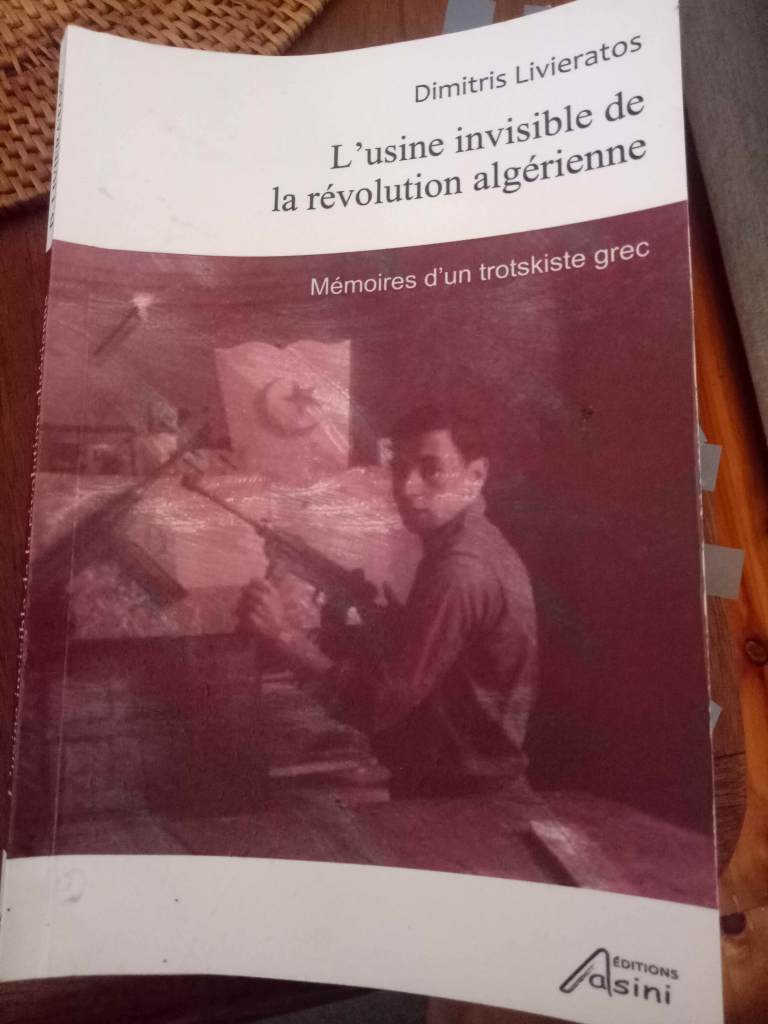

TRANSLATION(S)

There are plans afoot for Editions Syllepse to publish The Well-Dressed Revolutionary in French in 2024 . They are currently crowd funding to finance the translation. (Feel free to contact me hallgreenland@gmail.com if you are interested in contributing and I will forward details.) A Japanese translation is also underway.

A Greek translation has been mooted and would be ‘natural’ given Pablo was Greek and was intensely proud of both classical 4th and 5th century BCE Athens and the heroic ‘moments’ in contemporary Greek history (particularly the wartime resistance to Nazi occupation).

REVIEWS

The first review was from historian and critic Rowan Cahill – ‘An Odyssey or two’ – can be read here.

The second by Dave Kellaway – ‘The footloose revolutionary’ – can be accessed here.

The most recent review was posted on Facebook by John Scott in Adelaide and follows. Needless to say, I find it generous but hopefully accurate:

‘This is a treatment worthy of its complex subject and of the turbulent times he lived in; one would not need to possess an intimate knowledge of the Trotskyist movement to become absorbed in it, and in any case the author has provided a jargon-light and unobtrusive guide for the perplexed traveller.

One has not travelled far before one is absorbed in an atmosphere recalling Serge and Orwell, The Case of Comrade Tulayev and Homage to Catalonia, Europe and the hellish age of the dictators, and fallen into the company of some truly remarkable people, swimming against the current in an unequal struggle to reconstitute the communist movement against its arch-betrayer, Stalin, and to resist the tide of fascism which was engulfing Europe.

Between them Stalinism and Nazism picked off a high proportionof the leading militants of a movement which had all too few such people to lose: Rudolf Klement and Pantelis Pouliopoulos, Marcel Hic, Leon Sedov, Abram Leon among them, as well as hundreds of militants as dedicated and courageous whose names are forgotten.

Whatever criticisms are levelled at Michaelis Raptis/Michel Pablo, who can legitimately be arraigned for, e.g., self-deception on the prospects of the colonial revolutions of the 1950s/1960s, they were the misjudgements of a large, generous, and ardent personality whose optimism of will frequently exceeded his pessimism of intellect, and who was not content with the part of a spectator in the revolutionary theatre, but who got up on stage to render practical assistance, using skills of clandestinity acquired during the underground years of resistance to Nazism.

We are too prone, I think, to overlook the fact that, unlike ourselves, who know how things turned out, Pablo and his contemporaries were confronting a novel reality and grappling with it to the best of their ability. It is easy to see with the benefit of hindsight, which is as we know 20/20, that Pablo harboured impressionistic and unrealistic expectations of Ben Bella, Nasser, Tito etc; not so easy in the heat of the moment.

These were faults in a political person subjectively attempting to continue and creatively develop the legacy of revolutionary Marxism; but they were the faults of a combatant; if you never engage, you will never make any mistakes except the big one: the failure to engage.

It is not my intention to provide a blow by blow precis of the book but to encourage those interested in the history of that Thin Red Line which attempted to preserve, develop and pass on authentic revolutionary Marxism to acquire and read it; it is well worth the price of admission, and Hall Greenland is due a vote of thanks for this admirably well researched, extremely readable, and, despite the often grim nature of the story it has to tell, entertaining contribution to socialist history.’

BOOKSHOPS

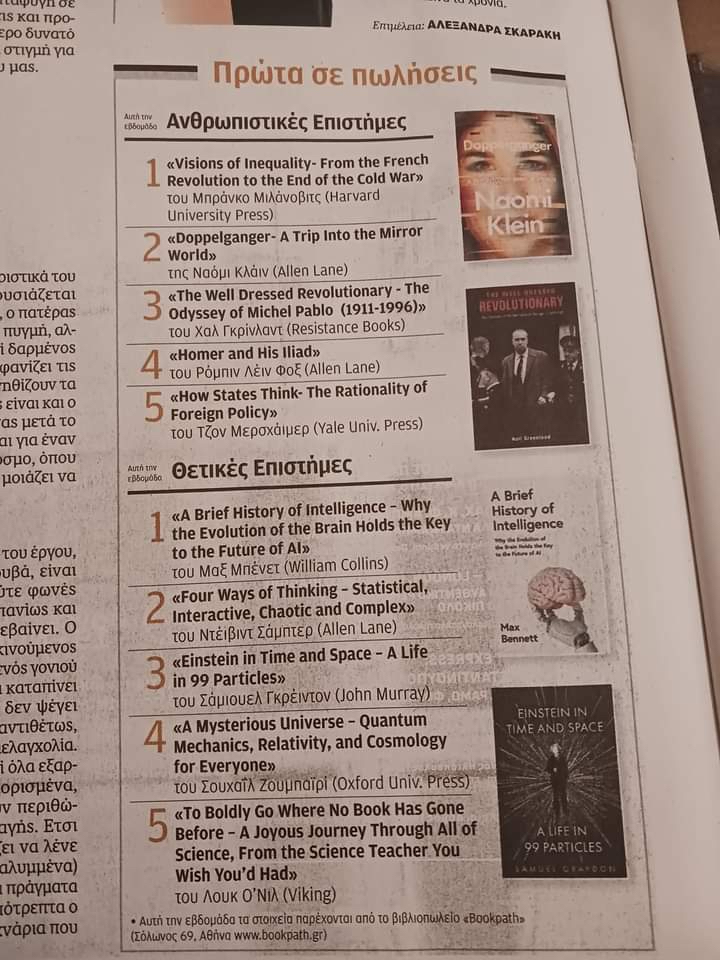

It’s certainly a battle getting into bookshops in Australia, especially if it’s a small publisher. Not so hard apparently in Athens where last Sunday’s edition of Kathimerini, the quality conservative paper in Athens, reported that The Well-Dressed Revolutionary was no.3 in the humanities’ best-seller list. Pipped for second by Naomi Klein!

PS encouraging responses continue to be received. This from 3 January:

Just finished your book, Hall. It was quite an education for me, as I lacked all but the most basic knowledge of Trotskyism and knew nothing of pablism. Also a sobering trip through the defeated revolutions of the 20th c. I responded strongly to Pablo’s embrace of self-management, feminism and decolonisation. And I liked your own pithy comments, often in brackets, that provided a subtle running commentary on how things actually turned out. Thanks a lot. Bill